History Timeline

1798–1867:

The Age of Rebellions

Before the famine, Ireland was already marked by repeated uprisings against British rule. Inspired by the ideals of the French and American revolutions, the United Irishmen rose in 1798, seeking to unite Catholics and Protestants in the cause of liberty. Though crushed, their struggle lived on in song, with ballads like Boolavogue and The Rising of the Moon.

In 1803, Robert Emmet led a doomed rising in Dublin. His execution gave birth to haunting verses such as Bold Robert Emmet, which transformed failure into martyrdom.

The Young Irelanders attempted another revolt in 1848, keeping alive the dream of national freedom, while in 1867 the Fenians carried the torch further, inspiring ballads like God Save Ireland and Bold Fenian Men.

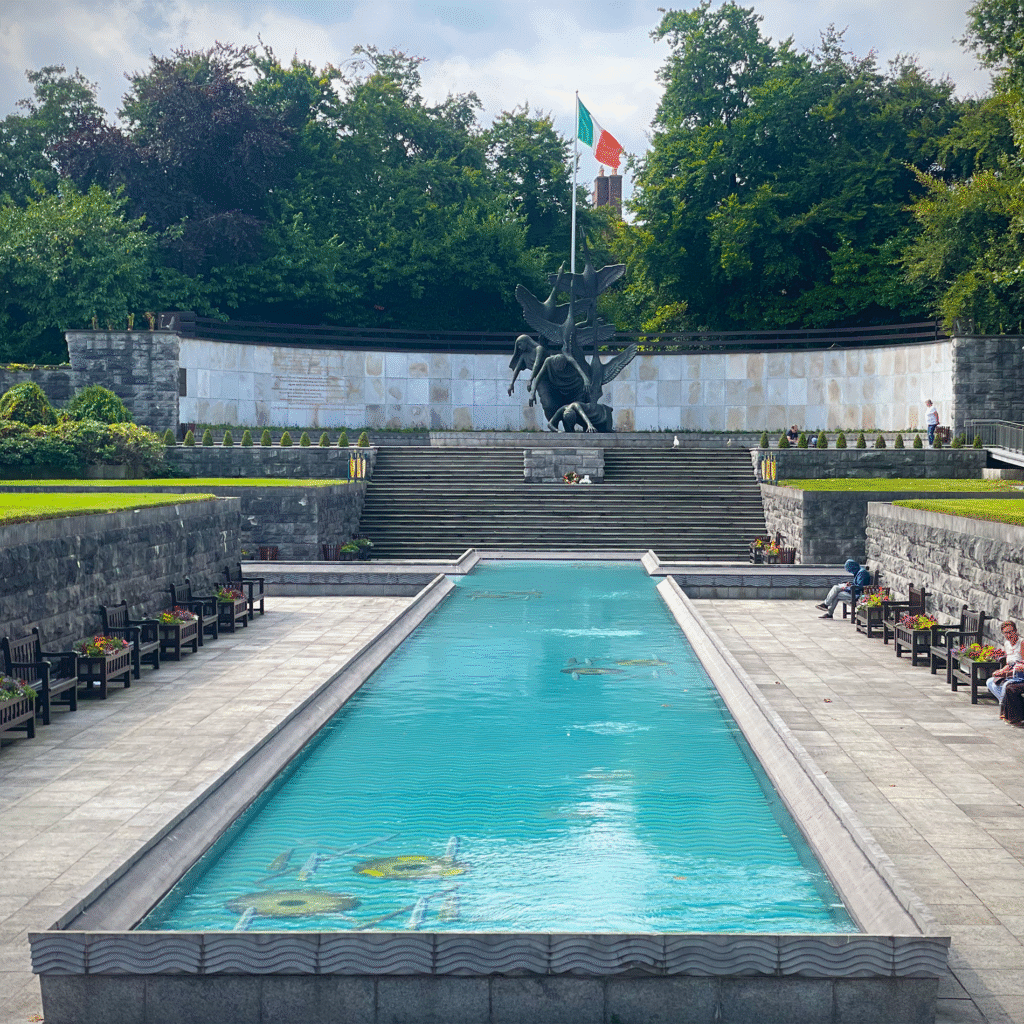

Although each insurrection ended in defeat, they left behind a legacy of poetry, music, and memory that sustained Irish nationalism. These rebellions, remembered in the Garden of Remembrance in Dublin, laid the cultural and emotional foundation for the struggles of the 20th century.

1845–1852: The Great Famine (An Gorta Mór)

In the mid-19th century, Ireland was devastated when potato blight destroyed the staple crop. Over one million people died of hunger and disease, while another million emigrated, boarding famine ships bound for America, Canada, and Britain. Whole villages were emptied, and the rhythms of rural life collapsed.

The trauma of the famine entered deep into Irish cultural memory, carried forward in song and story. Laments like Skibbereen gave voice to loss and anger, recounting dispossession and exile. Later, The Fields of Athenry became a modern anthem of remembrance, echoing the despair of famine and forced deportation.

Traditional sean-nós singing also served as a vessel of mourning, its unaccompanied style mirroring the stark grief of the period. Through these songs, the famine’s silence was transformed into sound, ensuring that the memory of An Gorta Mór would never be forgotten.

1858: Founding of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB)

In 1858, the Irish Republican Brotherhood was founded. It was a secret organisation, working underground, with one clear goal: Irish independence. Members risked their lives to plan uprisings and keep alive the hope of freedom.

Music carried their message when open speech was too dangerous. Ballads like The Bold Fenian Men and The Rising of the Moon gave voice to their struggle. These songs spread quietly from home to home, turning whispered rebellion into shared memory.

1879–1882: The Land War

Across Ireland, tenant farmers lived under the shadow of landlords. Rents were high, families were poor, and eviction was always a threat. In 1879, a new movement began — the Land League — giving voice to those who had long been silent.

Farmers gathered at meetings, marched in protest, and refused to pay unjust rents. Their actions shook the countryside and became known as the Land War. For many, it was the first taste of collective power.

Songs carried their struggle from village to village. Ballads like The Bold Tenant Farmer told of resistance and dignity, turning the hardship of rural life into a fight for justice.

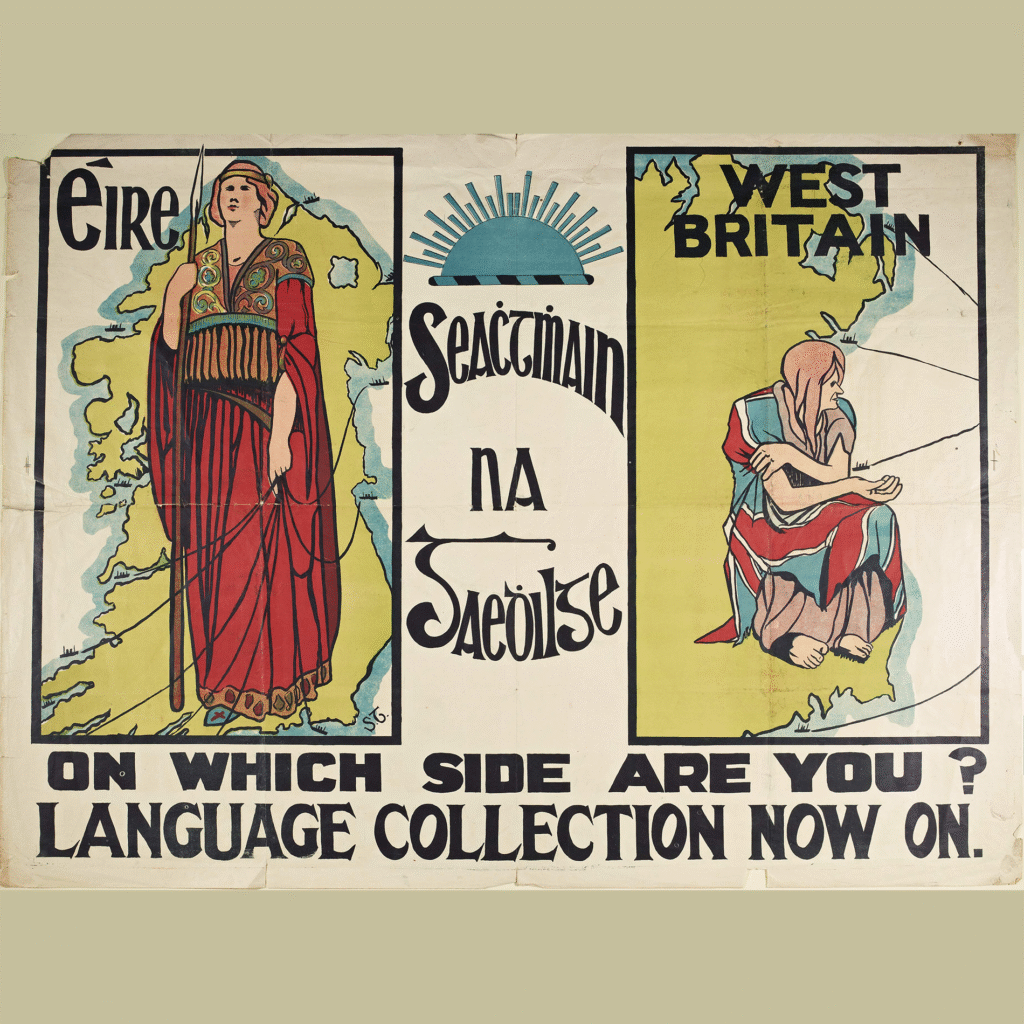

1893: The Gaelic League

By the late 19th century, the Irish language and many traditions were fading. English was the language of schools, of power, and of daily life. Something had to be done to protect what was left.

In 1893, the Gaelic League was founded. It gave new energy to the Irish language, to storytelling, and to music. Festivals and gatherings encouraged people to sing in Irish again, to perform the old sean-nós songs, and to celebrate Irish culture with pride.

Songs like Róisín Dubh and An Spailpín Fánach were brought back to life. Old nationalist ballads such as A Nation Once Again and Óró, Sé do Bheatha ’Bhaile found new audiences. The League made sure that music was not only entertainment, but also a way of keeping identity alive.

1913: Dublin Lockout

In 1913, Dublin became the centre of a great struggle between workers and employers. Led by trade unionist James Larkin, thousands of workers went on strike, demanding fair pay and better conditions. In response, employers locked them out of their jobs.

Families faced hunger and hardship, but the fight for dignity continued. Protest marches filled the streets, and violence broke out as police clashed with the crowds. The Lockout became a turning point in Irish labour history.

Songs gave courage to the movement. Street ballads, and later songs like James Larkin, celebrated the workers’ cause and turned their suffering into solidarity. Through music, their fight was remembered not only as a struggle for wages, but as a struggle for justice.

1916: The Easter Rising

At Easter in 1916, Irish rebels seized key buildings in Dublin and declared independence from Britain. The fighting was fierce, and after a week the rebellion was crushed. Its leaders were executed, but their sacrifice gave new life to the dream of freedom.

Poets and rebels stood side by side in this struggle. Pádraig Pearse, both teacher and poet, saw revolution as a way to create not just a nation, but a cultural rebirth.

Songs and poems kept the memory alive. Ballads like The Foggy Dew and Grace told of courage and love, while Óró, Sé do Bheatha ’Bhaile became a rallying cry. Music and poetry together turned defeat into inspiration.

1919–1921: War of Independence

After the Easter Rising, the call for independence grew stronger. From 1919 to 1921, the Irish Republican Army fought a guerrilla war against British forces. Ambushes, raids, and reprisals spread across the country.

The conflict ended with the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which created the Irish Free State. But it also left the country divided, setting the stage for civil war.

Songs gave voice to this turbulent time. Ballads such as Come Out Ye Black and Tans mocked British forces, while Kevin Barry and The Men Behind the Wire honoured young fighters and martyrs. Through music, the war was remembered not only as a military struggle, but also as a fight carried in the hearts of ordinary people.

1922–1923: The Civil War

The Anglo-Irish Treaty brought freedom to part of Ireland, but it also brought division. Some accepted the Free State as progress. Others rejected it, saying it betrayed the dream of a full republic.

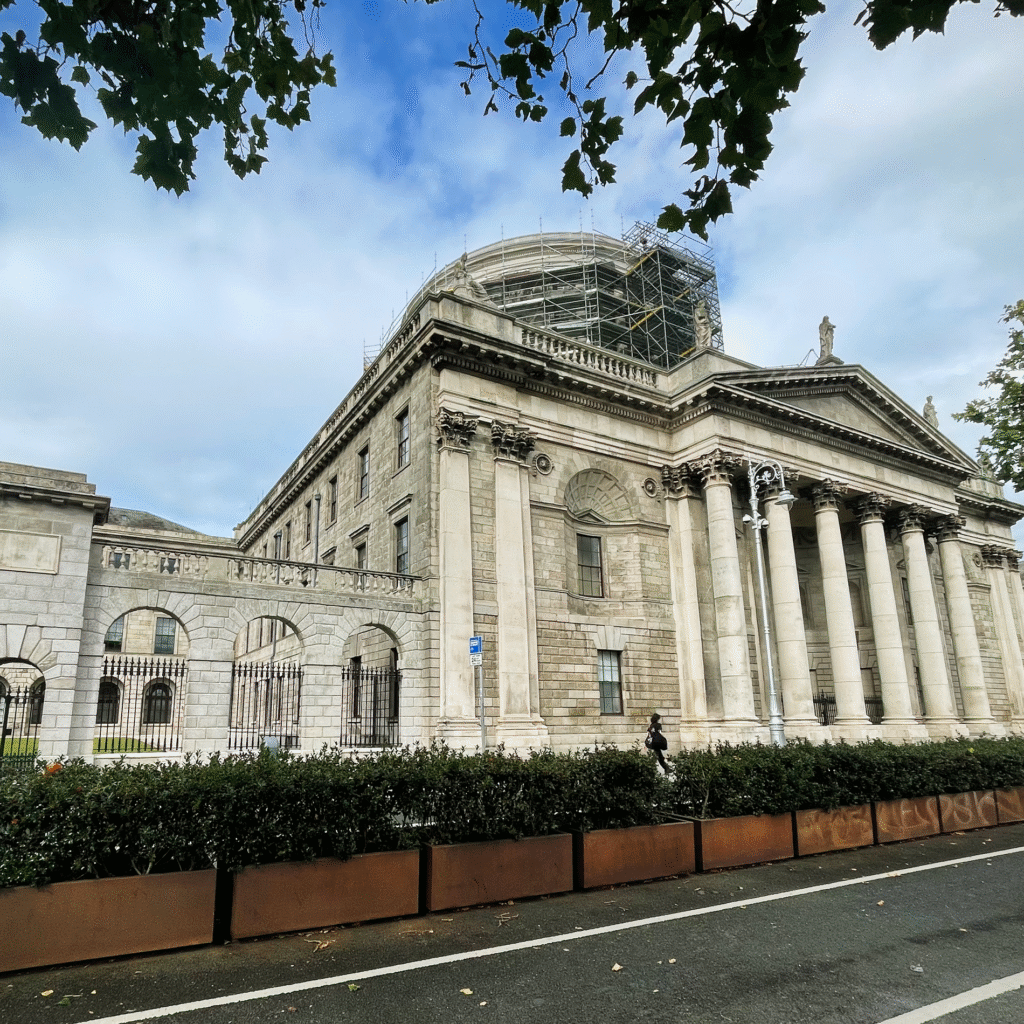

In 1922, former comrades in the War of Independence turned against each other. Cities and villages became battlegrounds. The Four Courts in Dublin were shelled, and executions on both sides deepened the wounds.

Unlike earlier struggles, the Civil War gave rise to few songs. It was too painful, too divisive, for ballads to be sung openly. A handful of laments, like The Ballad of Rory O’Connor, whispered of grief. But the louder voice was silence — a silence that revealed how deeply the conflict scarred Irish society.

1930s–1940s: Nation Building

After the Civil War, Ireland began to build its new identity. In 1937, a new Constitution was written under Éamon de Valera, giving the country a stronger sense of independence.

Culture was central to this nation-building. Radio Éireann, the national broadcaster, brought Irish voices and music into homes across the country. Traditional dance and céilí bands grew in popularity, and Irish films and theatre showed pride in the nation’s story.

Music and culture were more than entertainment — they were tools for shaping identity. They helped create the image of a united Irish state, rooted in tradition but looking toward the future.

1950s–1960s: Emigration & Folk Revival

In the 1950s, Ireland faced poverty and unemployment. With little opportunity at home, thousands of people left for Britain, America, and beyond. Emigration became part of everyday life, leaving behind broken families and empty towns.

Yet, as many left, a cultural revival was taking shape. In the 1960s, Irish folk music found a new global audience. Groups like The Clancy Brothers and singers like Luke Kelly brought ballads to international stages, dressed in their famous Aran sweaters.

Songs such as Spancil Hill and The Leaving of Liverpool gave voice to exile and longing, while others like Whiskey in the Jar celebrated Ireland’s lively tradition. For those at home and abroad, music became a bridge — a way to remember, to connect, and to belong.

1969–1998: The Troubles

In 1969, Northern Ireland entered a long and violent conflict known as The Troubles. It began with civil rights marches and soon turned into clashes between communities, the Irish Republican Army, and British forces. For almost thirty years, daily life was marked by bombings, shootings, and fear.

But even in violence, music gave people a voice. Rebel ballads carried anger and defiance. Christy Moore, Planxty, and The Wolfe Tones sang of resistance, while Phil Coulter’s The Town I Loved So Well spoke of personal loss in Derry.

Internationally, U2’s Sunday Bloody Sunday and The Cranberries’ Zombie turned Irish pain into global protest songs. Through music, the world heard both the struggle and the hope for peace.

1998: The Good Friday Agreement

After nearly thirty years of conflict, peace finally seemed possible. In 1998, leaders from different parties and communities signed the Good Friday Agreement. It ended most of the violence and gave Northern Ireland a new path forward.

The agreement was more than politics. It was a chance for reconciliation, for families to hope again, and for communities to begin healing.

Music reflected this new spirit. Songs of protest gave way to songs of peace. Seamus Heaney’s poetry spoke of hope and change, while artists and bands imagined a future free of fear. Music, once the sound of struggle, now became a voice for peace.

2000s–Present: Global Irish Culture

In the 21st century, Ireland has become a global voice. Traditional music is still alive, but now it blends with rock, pop, electronic, and hip hop. Artists like Hozier, Lankum, and Fontaines D.C. mix old roots with modern sounds, sharing Irish identity with the world.

Social change has reshaped the country as well. The legalisation of same-sex marriage in 2015 and the abortion referendum in 2018 marked a new chapter in Irish society. Art, music, and film reflect these changes, speaking about equality, mental health, and identity.

The Irish language is also returning in new ways. Groups like Kneecap and Imlé use Irish in rap and indie music, proving that tradition and innovation can live side by side.

Ireland’s story today is one of memory and renewal — a culture that honours its past, while creating new voices for the future.

2020s–Future: Emerging Trends

Irish culture continues to evolve in the 2020s. A new generation of artists blends tradition with innovation, bringing Irish identity into fresh spaces.

Traditional instruments like the fiddle, pipes, and bodhrán are now heard alongside electronic beats and digital sounds. The hip hop trio Kneecap mix rap with the Irish language, while artists like Denise Chaila and Loah bring new voices to Irish music and culture.

Digital archives, podcasts, and online communities are also changing how music and history are shared. Irish culture is no longer confined to one place — it now travels instantly across the world.

These trends show a living tradition, carried by young voices. Ireland’s story continues, always remembering its past, but always creating something new.